A deadly wind up

This post was written by James Nye

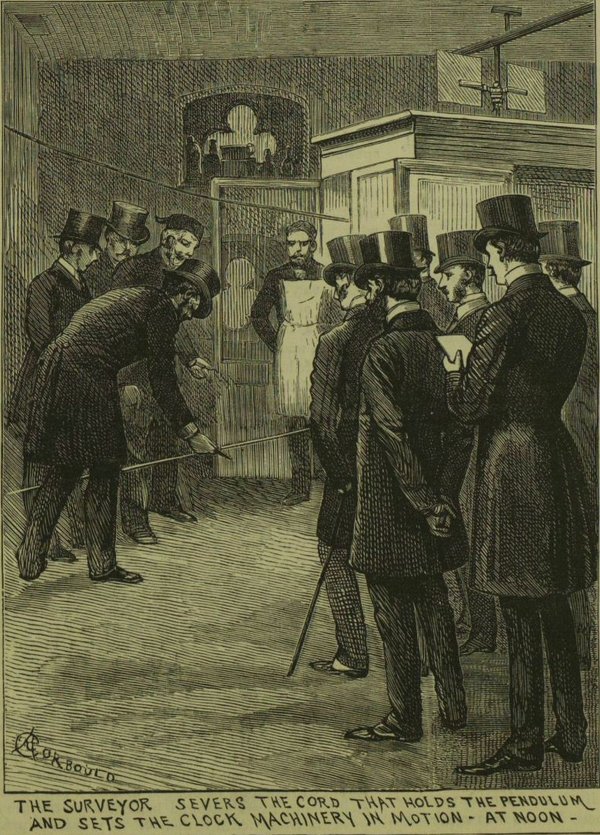

Horology is rarely gruesome, but on this occasion it certainly was. One of the largest and most impressive Gillett & Johnston clocks was installed in the Royal Courts of Justice in 1883. Its commissioning was accompanied by much pomp and ceremony, duly recorded on 29 December in the Illustrated London News.

The mechanism utilises a double-three-legged gravity escapement together with a remontoire, capable of excellent timekeeping.

Gillett’s were certainly irritated in May 1893 by a correspondent in the Horological Journal suggesting their clock had wandered by 15–30 seconds per day in mid-1892. They published their own record, showing frankly astonishing accuracy.

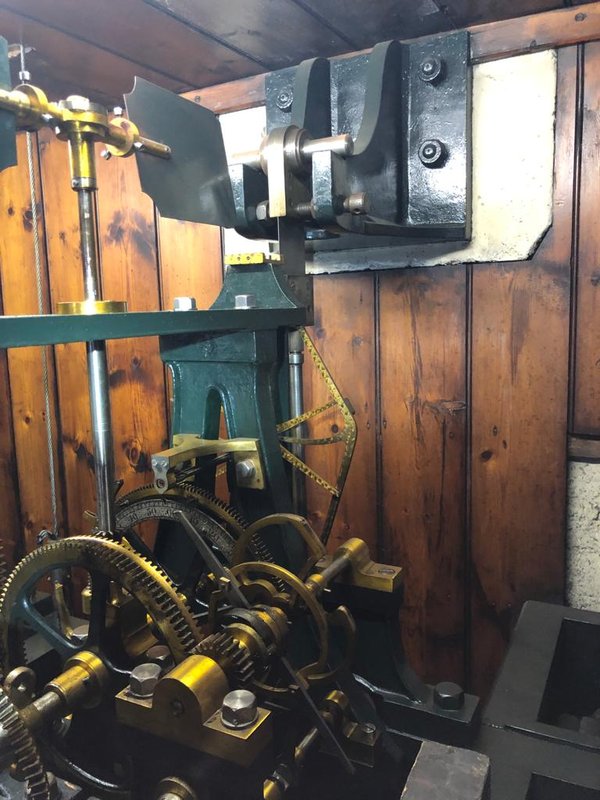

The clock will have involved a significant amount of labour to wind by hand, and unsurprisingly an electric winding motor was added later. The date of the motor remains unknown but it could well be the one shown here.

It sits on a twin railway track, which runs laterally in front of the movement, and on which the motor is moved opposite each of the three winding arbors in turn, engaged, and then energised to perform the winding of the weights.

The winding round at the Royal Courts has always involved hundreds of smaller clocks, as many as 800 at one time, as well as the large clock. In 1937, the 25-year-old Tommy Manners took over the job, and settled into a long-established routine, touring the whole complex, with a once-weekly visit to the tower to wind the big clock.

This lasted through the 1930s, through the Second World War, into the sunlit uplands of the 1950s, until the morning of Guy Fawkes’ Day 1954. Around 9am on 5 November, Manners climbed to the tower as usual. He was under notice not to get too close to the flywheel when winding was underway, but somehow his dustcoat was caught, the fabric becoming quickly wound tight. He was trapped, unable to escape, and if he cried out, no-one heard above the roar of the traffic below, as the clock motor, anaconda-like, squeezed the life out of him.

Something else not heard was the strike of the clock, resulting in two engineers climbing to the clock room some 90 minutes later to find out why. Somehow, Manners had become freed from the motor, and was lying beside it. Rapid first-aid was to no effect, and he was transferred to Charing Cross hospital, but in vain.

An inquest at Westminster a week later recorded a verdict of accidental death, noting that Manners had been alerted to the risks posed by the flywheel. One outcome of the tragedy was the fitting of the serious safety cage around the whole mechanism, visible in the accompanying image. A modern micro-switch arrangement now prevents the motor being operated except at a distance.

The original news caught the attention of many a newspaper editor round the world. Both the Guardian (6 November) and The Times (13 November) covered the incident. The Sarasota Herald (6 November) ran the story with the dramatic headline, ‘Clock Winder is Killed by his Favorite Clock’.

A sobering tale.